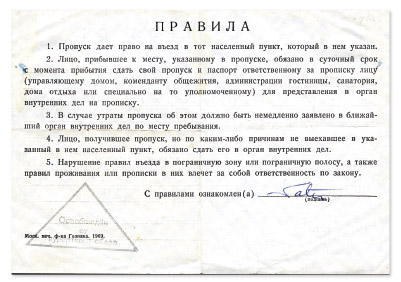

Besides the difficulty of travel abroad during Soviet times, movement within the country was also restricted. Estonia had 1,565 closed military features in 800 sites, taking up a total 87,147 hectares, including entire cities like Paldiski and Sillamäe. This made up nearly 2% of Estonian land area. The border zones – islands, the entire north coast and much of the western Estonian coast – were also closed. Outsiders had to apply for a permit to enter these zones. Even coastal dwellers were not allowed to put out to sea. Foreigners were not allowed to spend the night in Tartu, as a long-range bomber air force base was located on the outskirts.

TERMS OF USE OF THE BORDER ZONE PERMIT ISSUED FOR A TRIP TO HIIUMAA ISLAND. THE FORM WAS PRINTED IN 1969, AND THE PERMIT IN QUESTION WAS ISSUED IN 1981.

(HIIUMAA MILIATRY MUSUEM)

STUDENTS AT PÕLTSAMAA SECONDARY SCHOOL IN A MILITARY TRAINING CLASS DURING SOVIET TIMES. OCTOBER 1974. (NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

TALLINN POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE’S MILITARY DEPARTMENT. 1980s. (NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

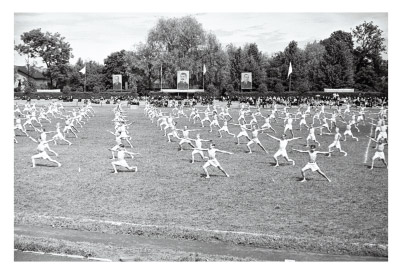

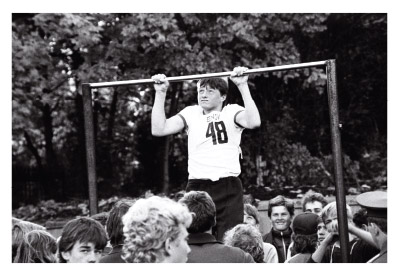

Physical education was an inseparable part of communist upbringing. Its aim was to instil Soviet patriotism in youth and prepare citizens for defending the country. Standards for physical aptitude were established for each age group. Companies and organizations had obligatory competitions, and running and skiing events for qualifying for these standards. The pan-Soviet physical culture classification “Ready for work and for the protection of the USSR” was a training programme used in the Soviet Union. It was introduced in 1931 and it existed until the Soviet Union collapsed. VTK was a supplementary part of the all-Union sports classification.

At universities, physical education was compulsory in each of the first four years of study. Every institution of higher education had a physical education and sports department.

A MASS BOYS’ GYMNASTICS EXERCISE AT THE SUMMER SPORT TOURNAMENT FOR SCHOOLCHILDREN IN 1951.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

A SOVIET ESTONIAN SPORT TOURNAMENT FOR THOSE SUBJECT TO BE CALLED UP AS CONSRCIPTS. TALLINN. OCTOBER 1987.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

PHYSICAL EDUCATION WAS AN INTEGRAL PART OF A COMMUNIST UPBRINGING. PHOTO CREDIT: A.VIIDALEPP. 1953.

(DIGAR – THE DIGITAL ARCHIVE OF THE ESTONIAN NATIONAL LIBRARY)