NEW INDIVIDUAL HOMES IN VÄNDRA. OCTOBER 1956.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

EMPLOYEES OF PÄRNU BUS DEPOT AFTER NATIONALIZATION OF THE PÄRNU BUS LINE COMPANY. 1940.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

The regime took an ideological view of property and labour. State/public and collective/cooperative ownership was recognized as socialistic. Personal property was for satisfying citizens’ material and cultural needs. This category included earnings, savings, home or part thereof, home-based production, and household and consumer items and personal effects. A citizen’s assets could not be used to earn non-labour income. Non-labour income also included income from illegal work (such as unregistered home handicrafts or keeping more livestock than the allowable limit). The means of earning such gains were subject to confiscation. The early 1960s witnessed a campaign for confiscation of houses built and cars purchased for non-labour income.

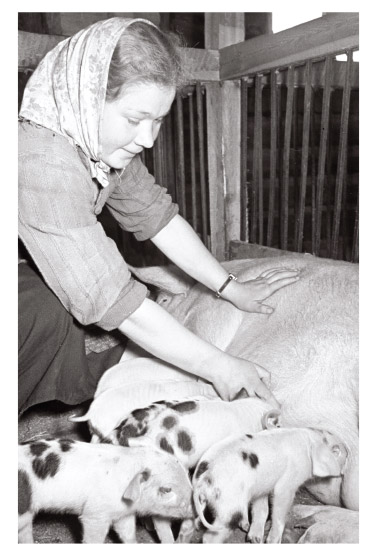

THE AGRCULTURAL ASSOCIATION (AN “ARTEL”) WAS ONE OF THE FORMS OF SOCIALIST COLLECTIVE LABOUR IN THE SOVIET UNION, AND IT GENERALLY PRECEDED KOLKHOZES. PIG FARMER AT THE 1st of MAY AGRCULTURAL ASSOCIATION IN VALGA RAYON, V. RISTOLAINEN, WHO HAD RECENTLY JOINED A KOLKHOZ ALONG WITH HIS FAMILY. VALGA RAYON. NOVEMBER 1956.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

The inability of collectivized agriculture to produce enough food bred a two-faced attitude: campaigns to check whether households were adhering to the allowed quotas and to confiscate the excess alternated with promotion of private production and developing of buying-up. As vegetables were an area of difficulty, collective horticulture was developed in cooperation between workers and white-collar personnel. Only buildings 10-20 m² in floor space could initially be constructed on the allotments set aside for the collective gardening initiatives.

The USSR also had a shortage of household items. Although permitted, home craftsmanship was subject to prohibitions and restrictions which it was an offence to disobey. Brokerage and commercial resale was also subject to harsh punishment. Prohibited individual labour activity could be punished by five years’ imprisonment and confiscation of the property.

Ideology was also behind differentiated taxation. The income tax rate in socialist companies were a maximum 13%, but independent farmers, craftsmen and clergymen had to pay up to 81%. In spite of the taxes, pensions were also different. Kolkhozniks had a higher pension age than state enterprise staff and the pension was smaller for the same salary. Farmers, craftsmen and clergy did not receive a pension, and orphaned children of such parents did not receive a survivor’s allowance. People did not take home their entire post-tax earnings – for a long time, state loan obligations had to be purchased. No interest was paid on these, and they matured tens of years later.

BUYING UP GOODS. INDIVIDUAL CATTLE OWNERS IN RAPLA RAYON DELIVERING MILK TO BE TRANSPORTED TO A CENTRAL BUYNIG-UP AREA. 1987.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE)