Stalin’s death did not mean the end of the regime’s crimes. 1956 was the year in which many of the Siberian exiles and Gulag prisoners started returning to Estonia. The return home was not without problems. For one thing, they were not to get their homes back and even faced obstacles returning to their hometowns. In many cases, this was not even possible, possessions had been scattered and redistributed. For the most part, relatives gave the returnees a roof over their head, as the deportees could not move back into their own homes. Although the deportees and political prisoners were released, they remained under KGB scrutiny practically until the end of Soviet rule. They continued to be regarded as an anti-Soviet element. They remained on file in the “register of sins” that could be used against them if needed.

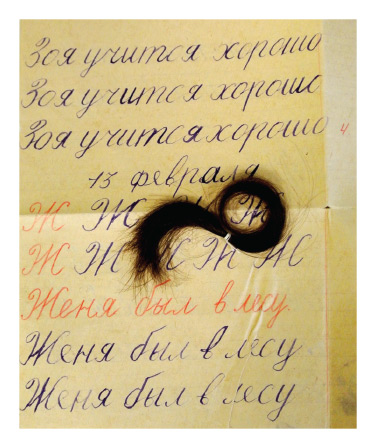

LOCK OF HAIR FROM SIBERIA. SECURITY SERVICES CHECKED PRISONER CORRESPONDENCE AND CONFISCATED “UNDESIRABLE” LETTERS. A LOCK OF A DEPORTEE’S HAIR AND THE FIRST ATTEMPTS AT RUSSIAN DID NOT MAKE IT BACK TO THOSE BACK HOME IN ESTONIA.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE. PHOTO FROM THE ARCHIVE. EIHR)

A NOTICE FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF THE ESTONIAN SSR INFORMING M. AINSAAR THAT HE HAD BEEN RELEASED FROM EXILE AND THAT HIS POSSESSIONS WOULD NOT BE RETURNED. 1957.

(MUSEUM OF OCCUPATIONS)

PUSHING A TACK INTO STALIN’S NOSE MEANT CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS AND A 10 YEAR SENTENCE.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE. PHOTO FROM THE ARCHIVE. EIHR)

THE FILE ON ONE DEPORTEE. 1949-1954.

(NATIONAL ARCHIVE. PHOTO FROM THE ARCHIVE. EIHR)

EXCERPTS FROM THE LEGISLATION OF THE ESSR SUPREME COUNCIL PRESIDIUM.1963.(NATIONAL ARCHIVE)

SCOPE OF BORDER ZONE IN THE MAINLAND PART OF ESTONIAN SSR. 1967. (REPRODUCTION)

TO LEARN MORE, CLICK ON AN ICON